In Defense of Effort

Photos by Camilla Danaher & Matthew Nehez

What makes a woman a “good feminist?” Navigating the politics of being a woman is tricky, and there’s no way to please everyone. Usually, however, I feel my views are mostly aligned with those of my friends, as I would hope theirs would align with mine. As such I was shocked when a close friend recently accused me of being a “fake feminist.” Not only hurt, I found the accusation embarrassing, as I felt I hadn’t lived up to this impossible standard set for me. I had heard before that my feminism was extreme, but never that it was not extreme enough. Yet, the insult was issued because I’d committed a moral failing as far as my friend was concerned: I had worn tinted lip balm. My friend explained to me that every action we take is political, and by wearing brown mascara and tinted lip balm, I was giving in to the objectification of women and the male gaze.

Women have always been judged by their looks, it’s true. However, it wasn’t always the case that beauty was equated with vapidity. Speaking of the French writer Violette Leduc, Jean Genet often said, “She is crazy, ugly, cheap, and poor, but she has a lot of talent.” That “but” is telling: literary talent here is equated to composure, beauty, and wealth. Leduc’s friend, feminist Simone de Beauvoir, was only slightly kinder, calling Leduc “brutally ugly and radiantly alive.” Is Leduc’s lack of conventional attractiveness why she’s less remembered than her contemporaries? It’s true she lacked the dignified grace and plain beauty of de Beauvoir, but she was a brilliant and innovative writer, and yet so many seem caught up in her appearance. Now, we would see her “ugly”-meets-talent story as the typical narrative.

When did this perception change? Hints of this shift can be seen in popular media. In the 1957 film Funny Face, Audrey Hepburn plays an incredibly smart, serious, academic woman, and is presented to us for the first time in an “ugly” dress and unstylish hair (though I think we can all agree she never looked less than lovely the entirety of the film). The typically beautiful model Hepburn’s character replaces in the film, Marion, played by Dovima, is played as stunningly gorgeous and comically stupid. She speaks in an unrefined accent and manner and can only read and understand comic books. Through the film, Hepburn is transformed into the woman with both beauty and brains, but as she makes this transformation, her character takes a distinctly less academic, less threatening turn. The more beautiful she becomes, the more watered down she seems.

Whatever caused its popularization, this strange stereotype took over both media and overall culture and was what I was exposed to growing up in the early 2000's. I was interested in science when I was younger, and in order to be taken seriously, I pretended not to care about my appearance much at all. I cringe looking back on my long, blunt, frizzy hair, the T-shirt and undershirt combinations worn with too-large blue jeans. Unsurprisingly, this look didn’t make me feel good about myself, and I was often jealous of other women. I would fret over how unfair it was that I didn’t look good while making no effort to look my best or even to take care of myself in basic ways. Still, I got enough flack from men in science for merely existing without their thinking I was frivolous as well. Young and unsure of who I was, the perception of these men mattered to me.

At twenty years old, around the time I decided science wasn’t for me after all, I read Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. This book spoke to me like no other was capable of doing at that moment, with its metaphorical fig tree becoming an image that would haunt me up to this day. Esther, a thinly veiled Plath, was beautiful and intelligent, but troubled mentally too. She was a complex human being who enjoyed and cared about fashion and even briefly worked for a women’s magazine, like Plath, but didn’t care for the inevitability of married tedium that femininity brought at that time. Esther bought expensive gowns during her employment at the fashion magazine, then felt empty and foolish looking at them later in a depressed state. She felt guilty for her earlier enthusiasm, for being privileged to the pleasures her employment at the magazine brought.

Plath meanwhile was unafraid of nurturing her aesthetic side and frequently described particular outfits or accessories she liked in her extensive journals. Still, like most of us, she struggled with self-image. After a suicide attempt in 1954, she sought to reinvent herself into a less serious, happier woman, and signified this to the world by dying her hair a soft yellow blond. She wrote to her mother that her “brown-haired personality is more studious, charming and earnest,” and dyed it back to her natural color, but those blond images persist in the public perception, sometimes being discreetly used to make her work seem girlish and juvenile. This was a woman who clearly gave her appearance and the judging eyes of others much thought. She seems aware that the blonde made people perceive her as less intellectual and almost implies that the dying of her hair changed her personality for the duration of those three blonde months, as if others’ assumptions were projected onto her. She continued to take note of how she looked, as any photograph of her will show, but she had found herself emotionally and intellectually.

Plath and Hepburn eventually became my style icons. After deciding to pursue a degree in the less male-dominated study of Art History and coming out as a lesbian, I became less concerned with how men perceived me. This, ironically, is what led to my caring about my appearance. Coming out freed me, to an extent, of the male gaze that pervades and even dictates the media I consume and love. I could finally redesign myself into someone I was proud to be on my own, and I discovered that person to be someone who enjoys a sleek, classic, but practical style. And despite what some of my friends thought, this transformation came during a period when I also became more studious, creative, and introspective.

“The fundamental misunderstanding is this: beauty isn’t inherently an impossible set of standards set by others. Beauty can and should be about self-care and self-expression. ”

Dressing well, making an effort with my skin and haircare, and taking a few moments to myself to curl my hair or put on mascara are all acts of self-care. Deep in depression at times before, I couldn’t bring myself to care about how I looked, and often felt like I was slowly wasting away. And in the rural American town where I was raised, self-care was viewed with suspicion. Thinking, or appearing to think, you were better than the others was a social sin. Departing from the norm was cause for mockery from children and adults alike. This pampering of myself gave me a confidence I had never had before. I suddenly felt so much more self-assured. Looking in the mirror and seeing someone I was proud of was a much needed ego-boost. Caring feels almost revolutionary, making the judgment all the more hurtful.

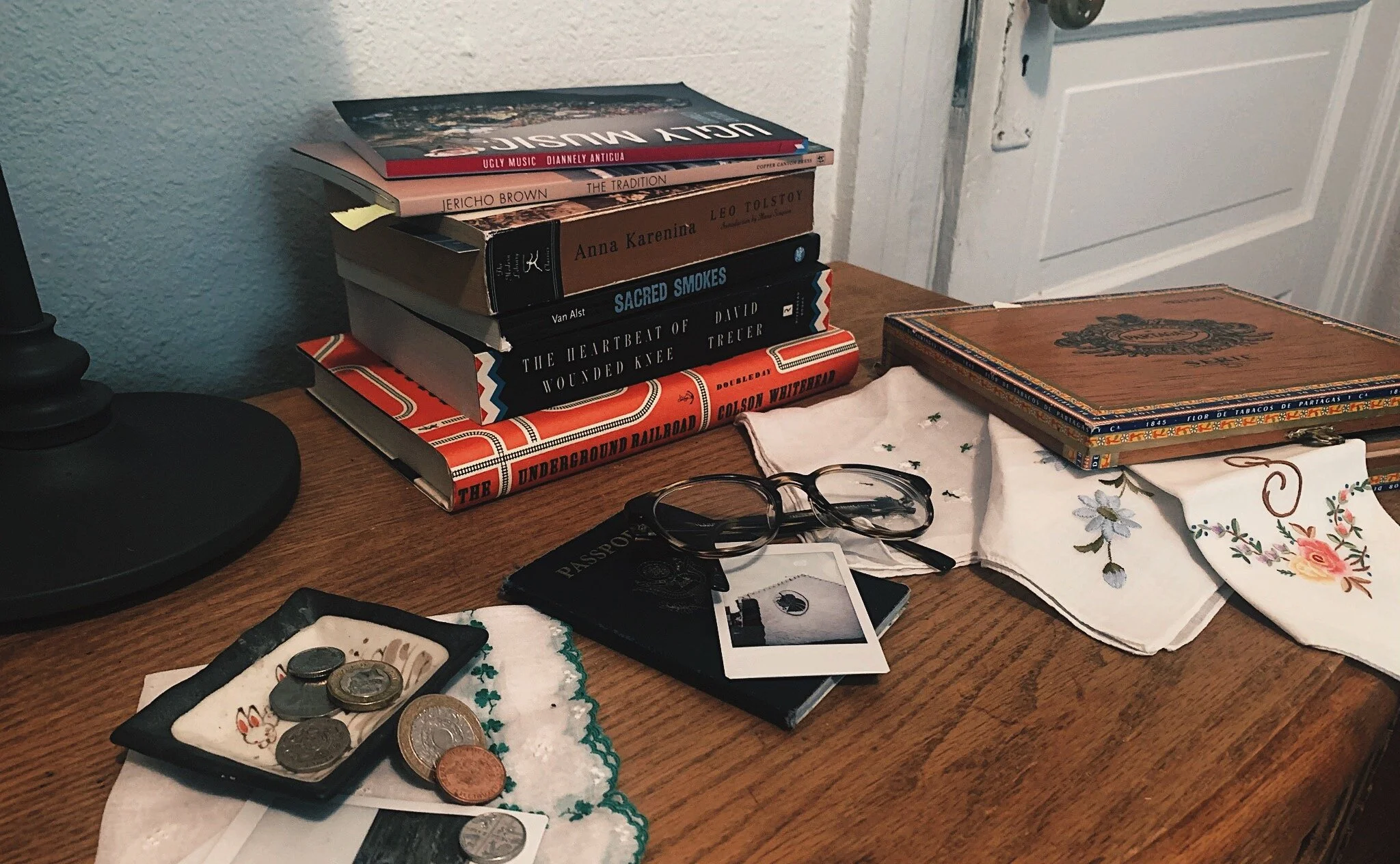

Fashion is often dismissed as a universal knowledge all women are born with, and not acknowledged as the complex form of art that it is. Like most fine arts, fashion is also a hobby for many amateurs like myself. Unlike other arts, fashion gets snubbed as merely a hobby. If an appearance conscientious woman is enough to make others scoff, it stands that an art form based on appearance would face derision. Women who follow the world of fashion do, contrary to popular belief, have depth. An interest in fashion, or appearance for that matter, does not suddenly render the mind devoid of logical function. I do crafts, read books, and study for my degree. I’m passionate about film and am learning Attic Greek. In short, I am a whole, well-rounded person who also cares about her appearance. If I don’t need a reason to enjoy reading, why but judgment would I need one for the journey of self-discovery that is cultivating a sense of style? The judgment those interested in fashion recieve can be hurtful. But I know who I am, and I’m not threatened by others not understanding that effort is not a bad thing.

And it is simply an effort I choose to make. Fashion doesn’t have to be expensive. My minimal makeup is affordable and lasts a long time, and if interested in perfume, one will do just fine. Nails can be done at home, and online second-hand stores like Poshmark make getting name-brand clothes as easy as shopping at Target. A put-together appearance doesn’t rely on the following of every trend. Wearing things that I feel good in makes them look instantly more fashionable.

Caring for the outward doesn’t mean that the mind is uncared for, or that this care is done for the sake of someone else. In fact, I find women who can juggle academics with work and family, as well as with appearance and personal refinement, more impressive than those who focus on one thing and judge others harshly for having different interests and priorities. Feminism isn’t the struggle to be a watered down version of ourselves, or of femininity. Women should be inherently respected for who we are as people, and assuming every polished woman isn’t deep or interesting is much less feminist than wearing lipstick.

The fundamental misunderstanding is this: beauty isn’t inherently an impossible set of standards set by others. Beauty can and should be about self-care and self-expression. As Audrey Hepburn — the woman who adored Givenchy and also spoke six languages — said, “Beauty is being the best possible version of yourself, inside and out.” Look for that best possible version of yourself, and show it off to the world. The sheer confidence you will feel from being your best will strengthen you against worrying about the opinions of others. In an age when women are bombarded with images of fabricated perfection, genuine confidence is revolutionary.

Camilla Danaher studies Art History and English at Arizona State University. She frequents galleries and coffee shops, where she writes short stories and essays.

In the latest of the series, Attic writer Madeline Baker gives us a glimpse into her nightly routine at a time where the world feels unstable.