Growing Up Through the Pages of Rome

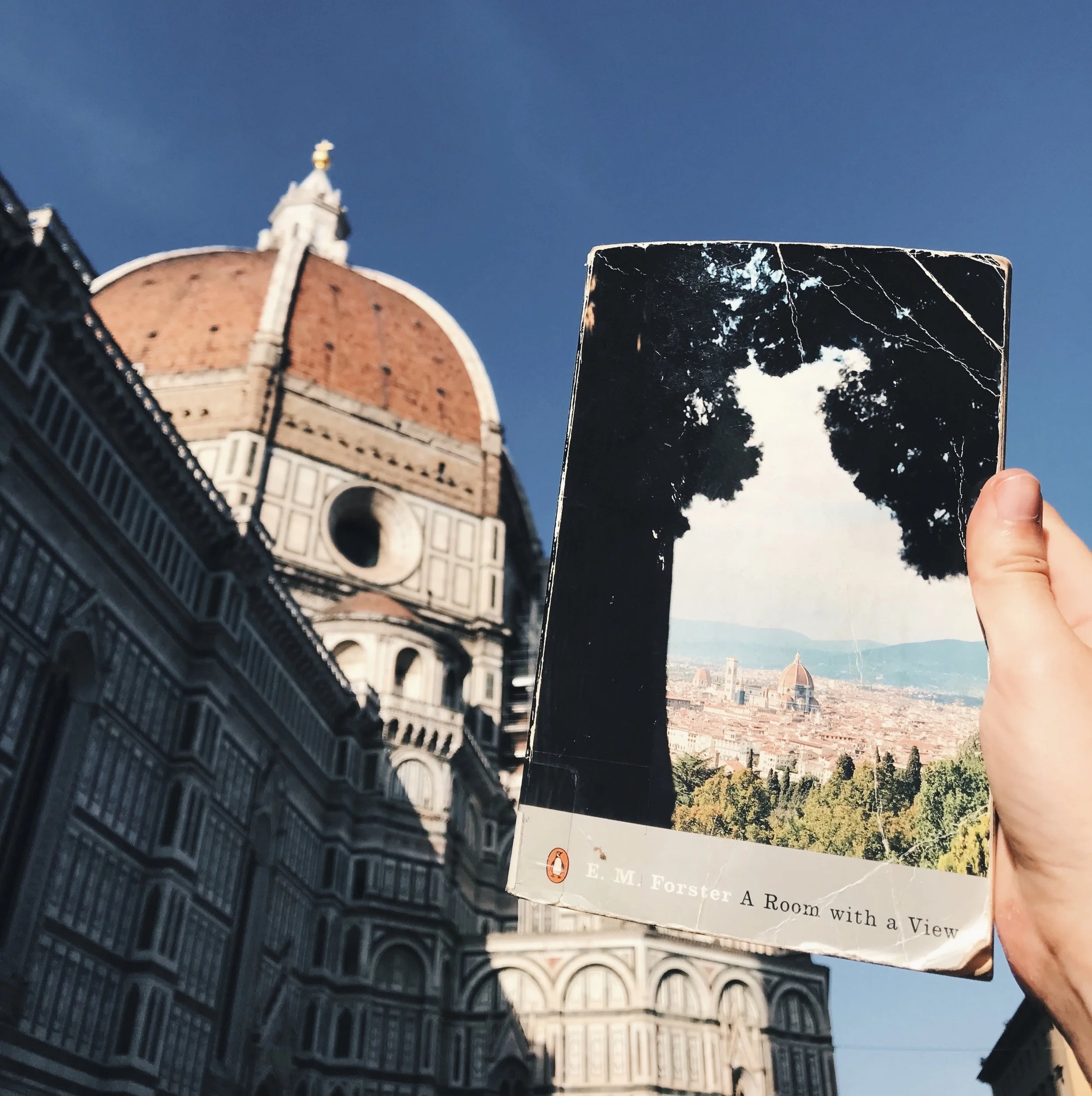

Photo taken by Olivia Gündüz-Willemin in 2015.

Growing up, I saw Rome only through two lenses: either I thought of the city and thought of the gelato I had on a school trip there once when it was so icy that the Colosseum closed, leaving all of us school girls to wear multiple hoodies at once while navigating tourist traps and pizza, or I thought of the ancient world which I saw in its museums and read about in a language now dead, which of course spanned a territory much larger than the modern city of today. As I got older, I began to read novels about Rome, and the city became something much larger than just its cuisine or its history. Rome became peoples’ everyday lives, as much as I could understand them, lived out against the backdrop of a city where my grandfather’s language is still spoken. I want to visit the city again, in spring or summer so that I don’t have to pay extra for luggage loaded with sweatshirts and coats, but in many ways, I feel like I have been many times since that school trip, in the depths of winter and the biting heat of June, July, and August, all through the pages of books.

Quiet Chaos, Sandro Veronesi

Sandro Veronesi’s Quiet Chaos begins on a remarkable summer day. Pietro and his brother, vacationing at a villa, save two people from drowning when they’re out surfing one morning. Returning to their holiday home where his fiancée and daughter were waiting for them, they discover that, in the short amount of time they were away, another life has been lost. Pietro returns home to Rome with his ten year old, Claudia, and without his fiancée, Laura. The novel is not about grief, not in any straightforward sense, because Pietro never really begins to grieve – not until the very end of the novel does he dare to open himself up to the process. Instead, he sits outside his daughter’s school, all day, every day for nearly a year. The book explores that period in between and the reader feels just as stranded as Pietro does, unsure about this narrator who can’t seem to express his own pain, whose fiancée we never get to know, not through memories or anecdotes, who can only wait for something to happen to jar him out of the strange routine he’s set up for himself. It is interrupted, but only by the people in Pietro’s life who both don’t understand what he’s doing why he’s doing and find him the only outlet for their own frustrations, their own problems, their own stories. Quiet Chaos is a waiting room novel after the fact. But it’s also funny, tender, intimate. The city narrows to a corner where Pietro sits outside his daughter’s school, to the people he meets, an old man who makes him pasta for lunch one day who understands his grief more than Pietro can do so yet, the young woman walking her dog who he’s attracted to, the sister of his fiancée who turns up to yell at him about he treated his almost wife. It’s a corner of quiet interspersed with the daily rhythms of the city, of children and their parents on their way to school or to the doctor, of too few parking spaces, of chaos. It’s also a corner where people in the city, rushed or worried or struggling, show Pietro compassion and grace in a way the thousands you pass on the pavement never can.

Four Seasons in Rome: On Twins, Insomnia, and the Biggest Funeral in the History of the World, Anthony Doerr

‘But in Rome, I’m learning, practically everything is set in opposition to something else—not only its most famous baroque architects, but its founding twins, the crypts beneath its churches, the hovels next to its palazzi, the empires within empires. Alleys rear and twist and cough up their cobblestones like big, black molars. […] I look up and realize I have been here before. Still, I’m lost.’

Like me, Anthony Doerr went to Rome thinking of the ancient world, a wolf feeding her two cubs. He was going with his own twin boys, only a couple of months old, on a fellowship awarded to him by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Four Seasons in Rome: On Twins, Insomnia, and the Biggest Funeral in the History of the World is his love letter to the city he and his family lived in from one November to July. In that year, a Pope dies. His babies grow and he struggles to sleep. People admire his twins in the street. He walks. He tries to write. The book is both a history of the city and of his just begun family. It’s written beautifully, in prose that will make you want to buy a flight and go to Rome yourself. Doerr reads Pliny and visits the Pantheon, like I once did, but he also buys bread and learns to greet people in a new language. He manages to steer a pram through the narrow streets and navigates a hospital trip when his wife gets ill. It’s hard to describe this book, because nothing momentous happens at all and yet everything is momentous. Everyday life becomes a marvel, because it is transplanted into a new country and culture. Because Doerr learns not only the history he’d known Rome for, but the histories a city like Rome hides: of its vendors and doctors and professors and the foreigners for whom it is a point in their journey.

In Other Words, Jhumpa Lahiri

The book set in Rome I would most highly recommend is one which is not really about Rome at all. Though set in the city, Jhumpa Lahiri’s In Other Words is about language, about its ownership and history. Neither the Bengali her parents speak nor the English she grew up with feels, to Lahiri, like it belongs to her completely. Italian however, which she was first introduced to when she took a trip with her sister at the age of twenty, armed with a pocket dictionary and not a guidebook, felt like a space in which she could start all over again with no expectations except the ones she gave herself and a freedom of choice she’d never had before. She moves back to Rome years after this first trip, in 2012, with her husband and children, and writes only in Italian for a year. She does not only want to speak the language: ‘Yet it’s not sufficient, or even satisfying, merely to collect words in my notebook. I want to use them. I want to draw on them when I need them. I want to be in contact with them. I want them to become part of me’. In Other Words itself was written in Italian and translated by Ann Goldstein, rather than by Lahiri herself. At the time it was published, critics worried they had lost a Pulitzer Prize winning author to another country’s language and literary culture. They were relieved when she returned to the English language, afterwards, when she packed up her bags and books at the end of In Other Words and flew back to the U.S. They were missing the point. Of course a year writing in a language would change how Lahiri wrote in English. Of course Lahiri is a highly talented writer whose work in English is worth the appreciation those critics give it. But even if Lahiri had continued to write in Italian, to have her work translated for her audience back in the country she called home for so many years, we would not have lost anything. Instead we find a writer who understands and contemplates language in a way translators do, with a precision and a thoughtfulness which is evident in every sentence she’s written in In Other Words. And Lahiri’s own creativity is clear in whatever language she writes in. Her bravery, too.

It’s impossible to write about Rome without mentioning some Italian writers, too, whether or not they write about the city. Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels are now so famous they hardly need introduction. The story of two girls who grow up in the same town but follow very different paths through life spans four books, but I inhaled them, as most people do when they’ve started the quartet, falling in love with Lena and Lila and just as much with the Naples of their youth. Ferrante’s Pisa, by contrast, where Lena studies after high school, is there only as a counterpoint to the girls’ Naples. It is the world of intelligentsia, where Naples is one where little girls aren’t allowed to stay in school. It is the world of the bourgeoisie and the elite, where the friends’ Naples is one of poverty and shoemakers and neighbourhood bad boys. It is bleak and grey compared to the place where Lena grew up where she knew anyone and everyone, where Lila was, beautiful and clever and undefeated. Since Ferrante’s novels have been published, Naples has seen a new type of tourist: the fans of the novel who visit the places mentioned in the books. A TV show has also been released recently, one I plan to spend the summer watching. At the moment, I’ve just started Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon traces the life of one family, the author’s own, between the 1920s and 1950s. Their life is recognisable to anyone who grew up in a large, boisterous family: her mother’s name for the author as a teenager is ‘Hurricane Maria’. But behind the dinner table conversations and family holidays skulks the shadow of the rising tide of Fascism, one which would eventually drive Ginzburg from her own country.

I haven’t been to Rome in years, but it doesn’t feel like it. Rome feels like a character I know like Lena or Pietro or the teenage Natalia. It is different each time I return to it, like any city, and yet recognisable, as Elena still is as an anxious child when she’s fifty, as Pietro still is when the year has cycled from one summer to another and this time there’s no chance of rescuing anyone but himself. And it’s still, too, history, of an ancient world and everyday people and a language and lemon trees.

Tilly Nevin completed her degree in English literature at the University of Oxford last year and plans to do an MA in Comparative Literature next year. After finishing her degree, she moved first to Germany for an editorial internship and then to France, where she divides her time between teaching overexcited children, city hopping on trains, trying to learn new languages and attempting to find the perfect café in which to lead the life of a young French existentialist (with more cake involved).

Continuing our unofficial series on Italy, Tilly Nevin travels to Rome through the pages of favorite pieces of writing.