Discussing The Cult of Donna Tartt

Portrait by Rachel Tay, Collage by Raquel Reyes.

Donna Tartt needs no introduction. It feels futile even, to refer to her as “American writer,” despite being just that, as though both descriptors have no business attaching themselves to a human that could be better described as an icon, or an institution — a well-known private individual choosing to grace us with a talent she could have easily kept to herself, perhaps fulfilling some potential wishes of continued obscurity. Instead she has written some of the most formative novels of the last century.

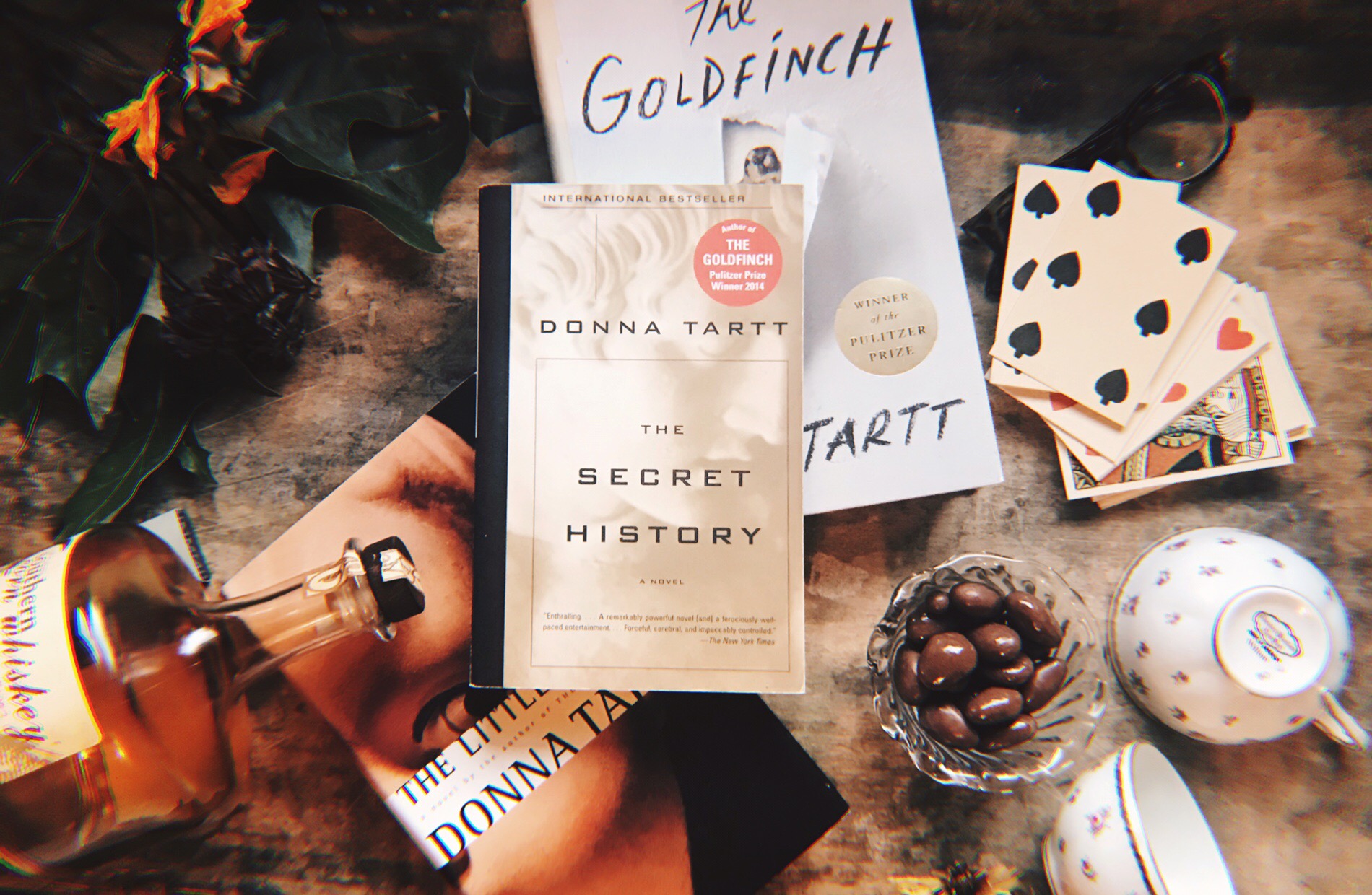

In terms of a cultural lexicon, it could be said that Donna Tartt has been with us for our entire lives. The Secret History, after all, was released in 1992, and though many of us wouldn’t read it for at least another decade, being ourselves born around that very same year, we cannot deny the stirring connection to Tartt’s debut novel, a work of literature that would spawn countless blog posts, mood boards, and even lifestyles for more than a few misguided souls. The Goldfinch, her most recent work, was released in 2014, a time when many of us were growing up and searching for our own meaning in the world. In a world still plagued by grief and terror, steeped in one crisis after another, its themes feel all the more relevant as a film adaptation takes the cultural forefront this weekend.

Discussing the writer for the first time on The Attic, our Culture Editor Eliza Campbell and featured contributor and artist Rachel Tay delve into the cult status of not only her works, but Donna Tartt herself, as well as the emotional holds and re-readability of her two most popular novels, the evolution of their interpretations, and the upcoming Goldfinch film.

“I’ve read The Secret History an embarrassing number of times.”

Rachel: Something that I’ve realised about Donna Tartt fans is that we tend to revisit her books, and more often than not, quite obsessively so. Every other fan I’ve talked to has spoken of reread counts that go well into the double digits — I personally make it a point to read either The Goldfinch or The Secret History at least once a year — so what do you think it is about Tartt’s novels that make them so re-readable?

Eliza: I know what you mean. I think I’ve read The Goldfinch every year since it was released and I’ve read The Secret History an embarrassing number of times. The Little Friend (2003) gets overlooked fairly often (and I’m guilty of that too) but it’s a pleasure to re-read. Really, I think it comes down to the detail that Tartt puts into her writing. She’s said in an interview that she takes so long to write because she’s essentially painting a huge canvas with a brush the size of an eyelash. Her novels are murder mysteries and thrillers, but, unlike other books in those genres, I don’t get sick of them once their secrets are revealed, because they are novels of observation first and foremost.

I’ve had the same copy of The Goldfinch since 2013 and it’s now absolutely covered with pencil underlinings and notes. When I re-read it this summer I noticed that I had very forcefully underlined sentences that seem fairly innocuous to me now. Clearly I’d had a different experience reading it in a previous year. For instance, when I was 15 and first reading The Secret History I used to take it extremely seriously but now I think of it as a bit more of a black comedy. Do you find new things every time you read it or is there something else that pulls you in?

“Tartt’s novels read [differently] every time you revisit them.”

Rachel: Of course, and that’s an experience I have with all texts — not just Donna Tartt’s. After all, I am a considerably fast reader, so there are always details that I miss here and there whenever I speed through a page; details that catch my attention and stun me later, not because they’re so consequential to the plot, but simply because they add such dimensionality to the characters on a second viewing. Do I need to know that Theo and Boris each had to get a shot on their behinds, because they were so malnourished by their parents’ neglect and their Vegas lifestyle? Perhaps not. But did the parenthesis in which Boris goes, “my bottom hurts,” make me chuckle, all whilst reminding me of how young and vulnerable these boys are? Sure. And it made me adore Boris even more than before.

But anyway, I’m absolutely with you on how differently Tartt’s novels read every time you revisit them. And I believe I had the same experience as you regarding TSH, especially now that I’ve survived four years of university education (having also first read TSH very committedly in my mid teens), only to realise how much of it was just pretentious posturing. I mean, “beauty is terror”? Certainly, one could trace such a sentiment to the Ancient Greeks, not to mention that there’s undeniably a lineage of aesthetic thought behind it. But boy is it pretentious, when you get a bunch of students just standing around delivering such aphorisms. Still, I think it is to Donna Tartt’s credit that she can meditate on these grand notions, even as she is poking fun at the people who are doing the pontificating. What do you think about this? Are critiques of Tartt’s so-called “pretension” or ”erudition” valid?

Tartt’s novels, and a selection of items mentioned throughout. Photo by Raquel Reyes.

“Elitism is confronted and questioned almost constantly throughout her works, admittedly with varying levels of success, but it is there.”

Eliza: I think if anyone started talking about how “beauty is terror” and all the other nonsense they ramble about in their Greek classes in one of my seminars at university I would leave right away. (No time for that, thank you.) But personally I’ve always found the criticisms of pretension and elitism aimed at Donna Tartt interesting. They’re certainly not unfounded, as she has written about white men with inferiority complexes who tend towards misogyny and confusing levels of homophobia. However, The Little Friend is about a young girl in Mississippi who’s interested in her family’s class. Its portrayal of southern life in the 1970s is hardly played up for aesthetic and it doesn’t cut corners on emotion to keep up with an airy superiority like The Secret History does. Elitism is confronted and questioned almost constantly throughout her works, admittedly with varying levels of success, but it is there. So really I think it is a fair criticism and one we should engage with if we’re going to enjoy her work but I certainly don’t think it’s a reason to stop reading her novels. Speaking of pretension and elitism and erudition, Donna Tartt was perhaps an unwilling subject for large sections of a recent Esquire piece rather provocatively titled The Secret Oral History of Bennington: The 1980s’ Most Decadent College. What did you think of the interviews? Do you think they revealed more about Tartt as a writer and should the information have any bearing on how we read her writing?

Rachel: Well, on the one hand, I don’t think anything divulged in that article was too out of the ordinary from what we already know about liberal, writerly programmes such as Bennington’s, as well as the hedonism, machismo, decadence, and trouble that tends to plague them. In fact, much of the piece reminded me of the eccentricity and the outlandish shenanigans for which the Iowa Writers’ Workshop is also infamous. So, having known about Bennington’s reputation and that of Donna Tartt’s cohort for quite some time, I don’t think the article really surprised me in general. But on the other hand, it was just slightly odd — but in a good way — to have some confirmation that Donna Tartt had always been that way. That she didn’t just wake up one day and decide to communicate with such rhetorical flourishes, but that, instead, she could always “converse in perfect wistful epigrams,” was always evasive and mysterious in her blazers, and was never pretentious but simply intimidatingly brilliant. If anything, the article probably affirmed the cult of Donna Tartt.

“She could always ‘converse in perfect wistful epigrams,’ was always evasive and mysterious in her blazers, and was never pretentious but simply intimidatingly brilliant.”

I must admit, however, that the story about Matt Jacobsen being Bunny’s inspiration did throw me off slightly, because I’d always been under the impression that Bret Easton Ellis was the sole mold for the character. In that way, it did disappoint me slightly to know that it might very well not have been Bret Easton Ellis that Tartt was scandalously trying to off in TSH. I wonder, could it still be possible? In any case, I’m well aware of the intentional fallacy, though I do, admittedly, also get some twisted sense of pleasure out of believing that Bret Easton Ellis was so insufferable that my favourite author would murder his fictional counterpart as soon as she had the chance — in the first pages of her first novel. What about you? How did you find the interviews and their revelations?

Eliza: It was an interesting read, and I do agree with what you said, it didn’t particularly reveal anything new, although it was enjoyable to have suspicions about Donna Tartt’s tendencies confirmed. I think what I cherished most was the new pictures we got of her. One looking girlish and sweet in her highschool yearbook (she looks like a character she would make fun of in one of her novels) and another of her looking absurdly effete during her years at Bennington.

Donna Tartt photographed by Mark Norris at Bennington, via Esquire; all rights reserved.

I think it’s good and proper she only ventures into the public eye during press for her novels or on very specific occasions but it’s personally nice to see more of my literary hero.

Speaking of which, I’m hoping we get a glimpse of her in one of her excellently tailored suits at at least one of The Goldfinch film premieres! Are you excited for the film? Personally, I’m a little nervous.

“In the immortal words of that John Boyega Instagram caption: ‘Don’t talk to me when I sit down to watch this! Don’t touch me! Don’t breathe in my direction! This is it!’”

Rachel: I still can’t believe that a film adaptation of The Goldfinch is a thing that now exists in the world! How did we even get here? Not that I’m complaining, of course. Or, well, perhaps I will be, if the film doesn’t live up to my expectations. Still, what do you think about the cast? For me, I was initially quite resistant to the idea of Ansel Elgort as Theo — he’s too built and smug-looking to play the scared and confused boy in my mind — but I think the glasses and hairstyle change has convinced me to at least give him a chance. On the other hand, Nicole Kidman as Mrs Barbour? Perfection.

Eliza: The casting of Theo was a big ‘I’ll believe it when I see it’ moment for me and I think Ansel looks fine. He’ll certainly be able to pull off the weirdness of Theo in the later section of the book. You’re absolutely right about Nicole Kidman and I think Sarah Paulson will be delightfully trashy as Xandra. For Boris, I think it will hinge on whether I can take the accents of Finn Wolfhard and Aneurin Barnard seriously, but I don’t doubt them as actors.

As we’ve been writing this together the first reviews of the film have come out of Toronto International Film Festival and they are overwhelmingly negative (which I find funnier than I should considering I’ve been looking forward to this since it was announced). I feel like a lot of critics seem to be critiquing things that are actually just the plot of the book and probably don’t translate very well to the pace of a film or a traditional Hollywood three-act structure. I’m exorbitantly excited about the film though and I really can’t wait. In the immortal words of that John Boyega Instagram caption: ‘Don’t talk to me when I sit down to watch this! Don’t touch me! Don’t breathe in my direction! This is it!’

Rachel: For the sake of everyone else reading this, let’s just say that Eliza and I have been discussing — thoughtfully, and definitely not losing it over — the first reviews of The Goldfinch on twitter. I’m not sure what to make of them still, considering the novel itself wasn’t all too well-received by critics either when it was first published. We’ll all just have to wait and see. Anyway, following Eliza’s lead, and to end off, here’s my favourite reaction to the TIFF reviews thus far (courtesy of Brandon Taylor): “Do film critics think that we care what they think about The Goldfinch? Shut up and let us watch the sweaterporn about beautiful people.”

Above all else, I suppose, it really is the beauty — of both humans and sweaters alike — that makes Tartt’s variously judged work so alluring and irresistible. Beauty, indeed, is terror…

For more on The Goldfinch film, we will be back tomorrow as Zoë G. Burnett shares a review in her list of Autumn films to watch!

Eliza Campbell is Culture Editor of the Attic on Eighth. When she’s not reading, writing, or in a rehearsal room, she loves to sit in galleries, libraries, and coffee shops listening to period drama soundtracks and watching the world go by.

Born and raised in the perpetually summery tropics — that is, Singapore — Rachel Tay wishes she could say her life was just like a still from Call Me By Your Name: tanned boys, peaches, and all. Unfortunately, the only resemblance that her life bears to the film comes in the form of books, albeit ones read in the comfort of air-conditioned cafés, and not the pool, for the heat is sweltering and the humidity unbearable. A fervent turtleneck-wearer and an unrepentant hot coffee-addict, she is thus the ideal self-parodying Literature student, and the complete anti-thesis to tropical life.

Annie Jo Baker explores the comfort found in the gentle monsters of our culture, with the works of Maurice Sendak, Charles Addams, Guillermo del Toro, Neil Gaiman, and more.