In Defence of Marie Kondo – What Does It Mean to ‘Spark Joy’?

Although I’d glimpsed the spine of Marie Kondo’s acclaimed The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying peeking out from the shelves of many a bookshop, I had always remained slightly sceptical to the effects it promised as a consequence of me sorting out my stuff – namely, revolutionising my entire existence.

It was in January of this year – at a time when I was both recovering from illness and experiencing the customary tidings of newness and clean beginnings which the chiming in of the new year brings along with it – that I was irresistibly pulled in by the Netflix adaptation of Kondo’s much-honed art.

Growing up, I possessed quite a certain cynicism towards those who claimed to be professional practitioners in the field of tidiness. As an admitted sentimentalist, I remained staunchly unmoved by trends towards minimalism. I viewed my possessions as very much an extension of me, and I cherished my trinkets, my 10-year-old birthday cards, and my expired train ticket stubs, thank you very much. However, it was to my surprise that that same defiant ‘thank you very much’ attitude is an element which is firmly embedded within the very approach Kondo advocates concerning tidying them up.

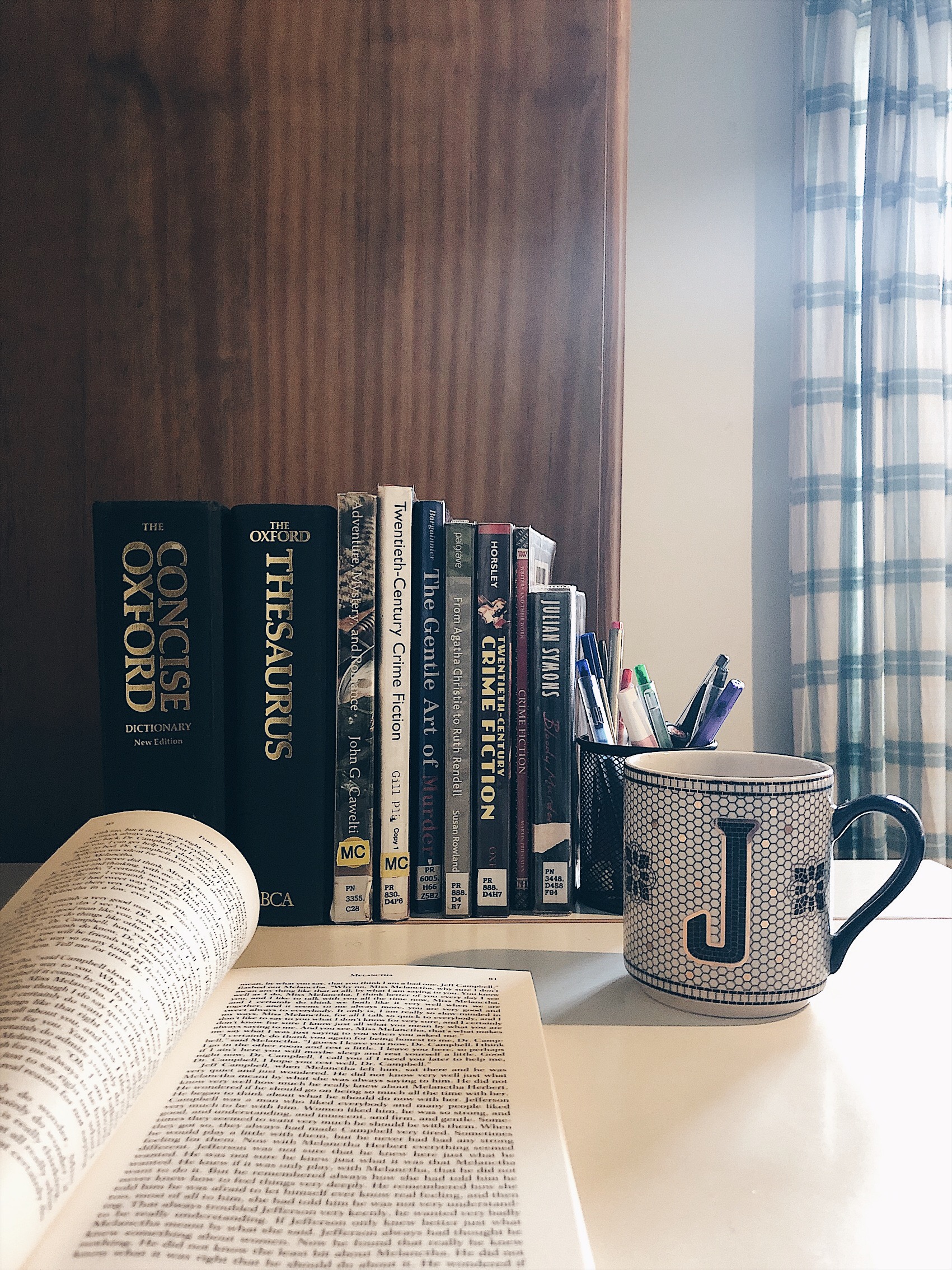

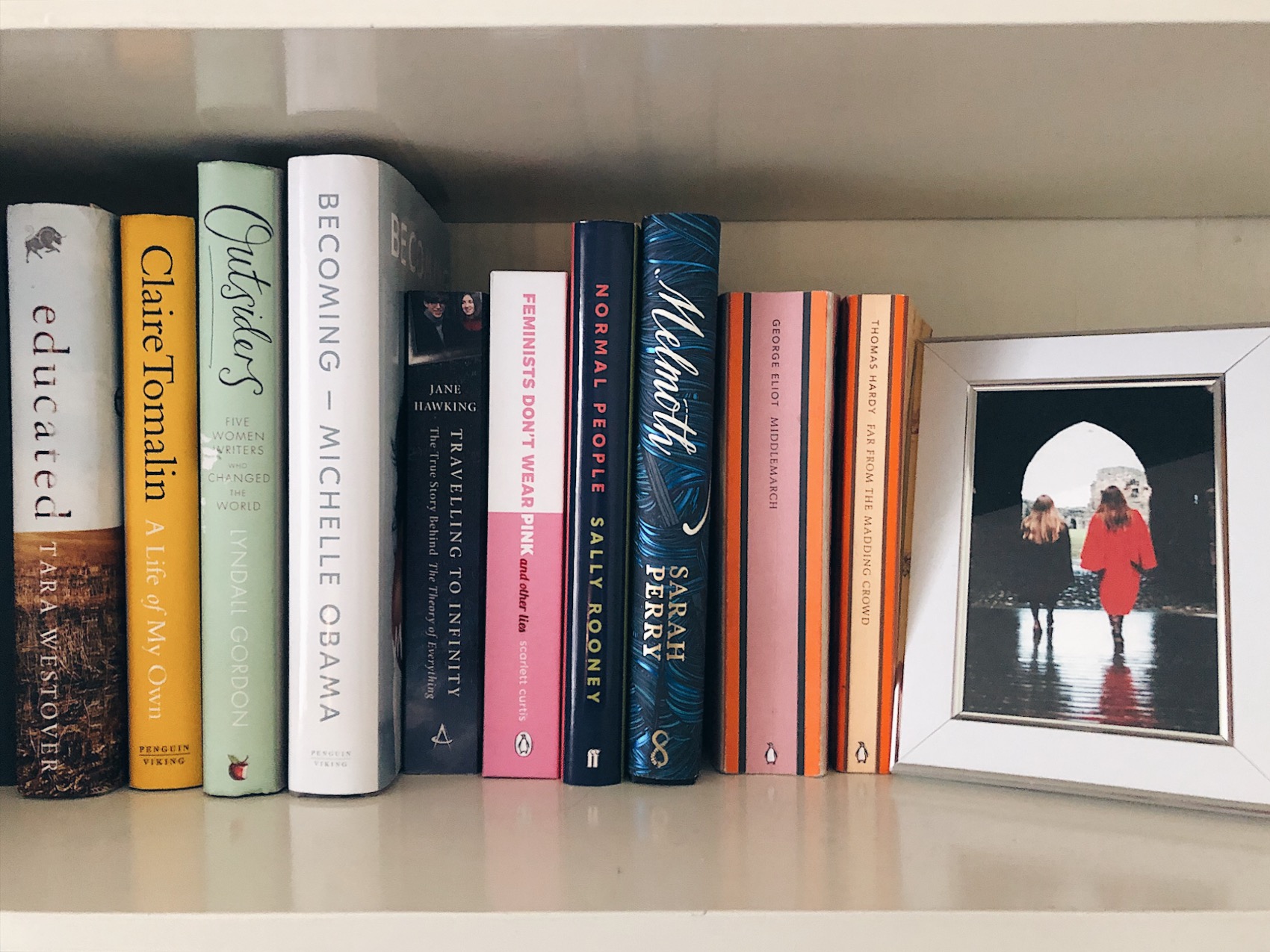

Her now infamous ritual of expressing gratitude towards our possessions before deciding whether or not to dispose of them is an element of the process which has attracted assertions of idiocy. Yet, when I pledged to attempt Kondo’s suggested practice, it was in my university bedroom – a space aesthetically characterised by a 4-year-steep mountain of academic notes I’d never managed to bring myself to dispose of (but had also never managed to sift through and sort out), as well as by a beautiful bookshelf. The latter displays a myriad of paperback and hardback treasures I’d painstakingly lugged from across the Irish Sea, either in the over-optimistic hope that I’d be able to read them during the final year of my English Literature degree, or (and more likely) to assure acquaintances/curious visitors/potential future renters of my excellent literary tastes during their visits.

“Yet, I think, to belittle Kondo’s suggestions is to underestimate the potential of joy.”

Kondo’s advice concerning books in particular has resulted in an army of seething bibliophiles emerging out of the woodwork and onto the spotlight of social media platforms. The sacred nature with which we tend to view our books, as valued narratives rather than mere possessions, has provoked outrage from many who find the notion of getting rid of them as being particularly incomprehensible. Yet, I think, to belittle Kondo’s suggestions is to underestimate the potential of joy. Joy is the determinate in philosophy Kondo proposes we adopt towards pillaging our possessions. Before deciding to discard an item, we are first encouraged to ponder whether or not that item sparks joy within us. And with that instruction comes the controversy. If we consider joy to be a state of optimum happiness, it begs the assumption that the emotionally diverse content of within many of our book collections are rendered incompatible with the ‘ideal lifestyle’ Kondo promises our efforts will direct us closer towards.

Those who have misconstrued Kondo’s advice have opposed it on the grounds that, if taken literally, we will be left with overly sanitised bookshelves, boasting only titles which make us simper uncontrollably at their sheer cheerfulness. What about the books that are explicitly unhappy? What about the books that challenge us, leading us to inconsolably gulping in between sobs, or the books whose words incite an automatic urge within us to hurl them across a room when we reach their final pages?

“Joy is distinct not only from pleasure in general but even from aesthetic pleasure. It must have the stab, the pang, the inconsolable longing.’”

Rather than interpreting joy as an exalted state of bliss, C.S. Lewis nicely accounts for its complexity, writing: ‘Joy is distinct not only from pleasure in general but even from aesthetic pleasure. It must have the stab, the pang, the inconsolable longing.’ These unquestionably physical by-products of joy encourage us to think of joy, not simply as gushing gratitude, but as highly powerful, at the very least as having the potential to be moving. Here, Lewis is also suggesting that it is not only conceivable, but in fact commonplace, that our experience of joy might even be painful. I also took it to suggest that the multi-faceted nature of joy means that the emotional roller-coaster stimulated by reading Thomas Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd is just as legitimate as the laughter I experienced in response to Adam Kay’s This is Going to Hurt.

“It was Lewis’ definition of joy that made me realise that an ‘ideal lifestyle’ does not necessarily call for a radical overhauling of the past.”

He goes on to write that ‘all Joy reminds. It is never a possession, always a desire for something longer ago or further away or still “about to be.”’ An aspect of so-called manic tidying which had previously overwhelmed me was the prospect of purging my things, so that only the things which were compatible with the person I wanted to be – rather than who I was – remained. As Kondo encourages us to think deeply about our ideal lifestyle before tackling our possessions, it was Lewis’ definition of joy that made me realise that an ‘ideal lifestyle’ does not necessarily call for a radical overhauling of the past. For me, if something ‘sparked joy,’ it had the ability to transport me beyond the present – and whether or not that was back into the past or further into the future was inconsequential. What did matter, however, was whether or not I wanted to be moved in that way.

Although Lewis’ comments on joy personally impacted my own tidying up, one of the aspects of Kondo’s process which I particularly value is her insistence upon joy’s subjectivity. When Kondo encourages someone to decide whether their possessions spark joy, she often insists that they will know within themselves what that means for them. By remaining uncompromising on joy’s subjectivity, Kondo is acknowledging that she – or anyone else for that matter – does not have any claim to a commercial monopoly on emotive experience.

“it is by no means prescriptive”

Therefore, while the approach Kondo recommends towards tidying is controlled by stages, it is by no means prescriptive. In fact, she recognises the emotional value of our possessions, to the extent that in the case of recently widowed Margie, she advised her to focus on sorting out her recently deceased husband’s belongings before moving on to her other items. The poignancy of instances such as this one really demonstrate the inaccuracy of accusations that Marie is simply on a one-woman mission to rid our lives of the very objects that make us human.

Aside from her palpable focus on joy, Kondo’s attitude towards tidying encourages us to cultivate other emotions, too. In an article outlining her daily routine, Kondo reveals: ‘as I’m tidying, I’ll give each item a heartfelt “Thank you” for helping with the day. Everything has a set place so it’s a smooth process. And, like that, the house is reset, which makes me happy.’ While to some the action of actively thanking an item might seem whimsical, even taking the time to mull over the impact my possessions have had upon my day in my head has provided me with an increased sense of gratitude. Getting into the habit of acknowledging my empty mugs as I take them from my desk to wash them, or as I file away that day’s readings, it has encouraged me to ponder just how much I have managed to achieve.

Ultimately, the highly emotive aspects of Kondo’s approach completely overturn any notion that she wants us to turn our bedrooms, our homes, and our personal spaces into soulless mausoleums, her overt acknowledgement of the subjective nature of joy allows us to escape any pressure that have to resemble carefully cultivated showrooms (unless, of course, we want them to!).

In offering a methodical approach towards emotional expression, Kondo has devised a way for the sentimental among us to balance aesthetics with practicality. And, by encouraging us to think, appreciate, and remember along the way, this can hardly be a negative thing.

Jessica Armstrong is a final year English Literature undergraduate at the University of St Andrews, Scotland. When she’s not on the silent floor of the library, it is likely that Jessica can be found getting audibly excited about the miraculous beverage that is a London Fog, scones, or student-run arts festivals elsewhere among the town’s three streets.