Travel Through the Pages: The French Riviera

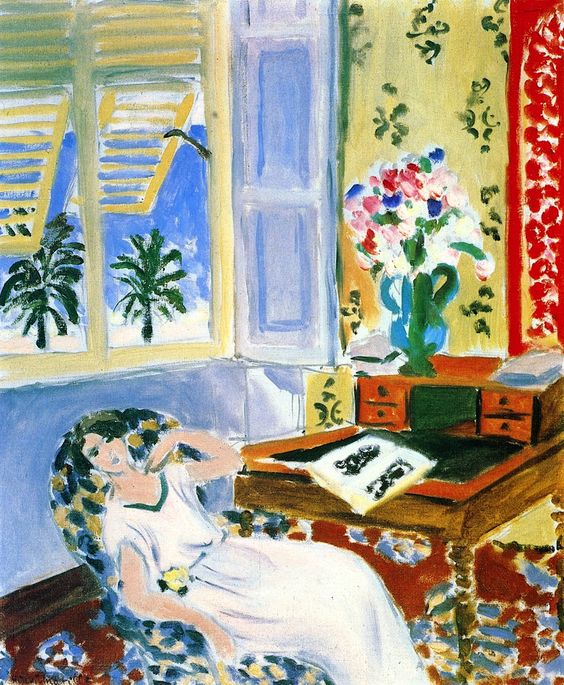

Henri Matisse, “Seated Woman, Back Turned to the Open Window” (1922).

So you’re stuck at home this summer, maybe working during the day, wishing you could get out of your small flat on the weekends to someplace that has a bit more of a breeze and a bit more of a summer feeling to it. Summer in the city has you down, heat wave after heat wave, with no movement in the air but tons of humidity and far too many moments where you think you’re actually, literally, finally going to combust.

Really, you wish you could pop back in time and (possibly) across an ocean or two and find yourself on the beaches of the Riviera. Colorful flowers, rocky cliffs, striped parasols, and maybe, a little sun-soaked romance. Clichés abound in summer, perhaps nowhere more so than through the mouths of the English-speaking in the South of France, where the seaside reality is perhaps a bit less glamorous than its presence in the media. (My most vivid childhood memory of the Riviera is of sitting in traffic and taking six sun-soaked hours to go from Monaco to Nice in August. It is, needless to say, better visited in the off season.)

Here, then, are some favorite pieces of media, from books to films to paintings, to get you from the overheated city to the French Riviera, seen here through the rose-tinted glasses of the English-speaking abroad. Consequently, actual French books and films that take place in the region – Bonjour Tristesse, La Piscine, Et Dieu… créa la femme, etc. – have intentionally been left out in this case but could be considered if you wish to add to your viewing/reading list. (For a far more genuine look at French culture, you can check out Milena Le Fouillé’s introduction to Eight Francophone Authors or stay tuned for less anglo-saxon-driven pieces in the future!)

✹✹✹

Cary Grant and Grace Kelly on set for To Catch a Thief (1955).

To Catch a Thief, Alfred Hitchcock

(film, 1955)

Appearing in our Summer Films list at the beginning of the season, To Catch a Thief is an Attic summer favorite for a reason. Taking place in Cannes in the mid 1950s, the Hitchcock film has it all. Jewel thieving, intrigue, romance, Cary Grant, and Grace Kelly. It’s sure to make you want to dive into a wavy body of water and beautifully dress up afterwards.

Still from To Catch a Thief.

✹✹✹

Transports Aeriens Maïcon (1920s), artwork by Jean A. Mercier. Planes play a significant role in the Riviera portion of Save Me the Waltz.

Save Me the Waltz, Zelda Fitzgerald

(novel, 1932)

Zelda Fitzgerald’s only novel, Save Me the Waltz was written in 1932 as the author was hospitalized for schizophrenia and prescribed to write for several hours a day as part of her therapy. The novel is often said to be inspired by her life with her husband – touching on numerous biographical elements – but it’s more striking as the predecessor to Tender is the Night. Beautifully written, it’s a favorite to pick up in the summertime – descriptions of flowers abound and a significant portion of the novel takes place in the South of France, where its protagonist Alabama Beggs engages in a memorable affair.

Zelda Fitzgerald as a teenager.

✹✹✹

A 2019 edition of Tender is the Night, revisiting the original 1934 cover art.

Tender is the Night, F. Scott Fitzgerald

(novel, 1934)

Like Save Me the Waltz, a significant portion of Zelda’s husband’s novel takes place near Nice, where its protagonists Dick and Nicole Driver rent a villa and surround themselves by many other Americans abroad. Tender Is the Night is by far Fitzgerald’s darkest and most complex novel, but it is also one of the most literarily satisfying.

A photo of Gerald and Sara Murphy, the couple that some argue inspired Tender is the Night, via a 1962 article from The New Yorker, “Living Is the Best Revenge.”

✹✹✹

Photo by Olivia Gündüz-Willemin

The Children, Edith Wharton

(novel, 1928)

So much American literature that transports itself to the South of France does so with a large dose of drama. Edith Wharton – never known for happy ending – is no exception. One of her oddest novels, The Children is the story of a group of seven children who run away from their parents, from the US to the Riviera to the Alps, but strike up a friendship with one of their father’s friends. The novel would no doubt be better if told fully from the perspective of the eponymous children rather than the family friend, but it is a memorable read nonetheless.

Alternatively, if you want a little Wharton with a good dose of New York as well as Riviera drama in it, then you can’t go wrong with The House of Mirth.

✹✹✹

Two for the Road (1967).

Two for the Road, Stanley Donan

(film, 1967)

The story of a long-married couple who travel through France to Saint-Tropez, Two for the Road is one of Audrey Hepburn’s least known but most memorable films. Both funny and dark, the film is set in 1964 and deals with the realities of marriage in the 1960s – that it is not always set for smooth sailing. Albert Finney and Audrey Hepburn play the Wallaces, and through a series of flashbacks, the couple examine and heal their relationship as they travel. As a bonus, the film features some of Hepburn’s best – and most-easily-interpretable-for-2019 – film costumes.

Two for the Road (1967).

✹✹✹

Picasso, 1962.

Matisse & Picasso

What is an imaginary trip to a locale without a dip into the artwork that it’s inspired? While many artists have traveled if not settled into the South of France – drawing inspiration from Provence (which remember, is not the same thing) or the Riviera – the most memorable, at least from a cheerful summery perspective to make up for the angst of the Americans, are Matisse and Picasso. Both artists took up residence in the region – Matisse from 1943 to 1948 in Vence and Picasso over the last thirty odd years of his life, most famously in Antibes. Picasso’s “Cote d’Azur” poster is one of his brightest, most colorful creations, and Matisse’s Riviera paintings are some of the biggest summer “MOOD”s in existence – women lounging, colorful flowers, serene waters that you want to dive into – all vibrant and soft at the same time.

“Interior in Nice,” Henri Matisse, 1922

Olivia Gündüz-Willemin is Editor-in-Chief of The Attic on Eighth. She is dedicated to reading her way through the world and trying to stay as calm as possible.

In a personal essay, Elizabeth Slabaugh visits the disappointments and realization of tempered dreams around traveling to Oxford after not being able to spend a semester at the university due to chronic illness.