A Room of Want’s Own: Brief Comments on Female Desire in Three Summer Reads (and One Excellent British Tragicomedy)

“[T]o want – and to know what she wants – is, for a woman, always a dangerously transgressive act.”

This past year has seen a plethora of new literature published on the state of female desire. From Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other, a stunning survey of black British womanhood, to Kristen Roupenian’s You Know You Want This (Roupenian, of course, of ‘Cat Person’ fame), it would appear that the advent of #metoo has now augmented unignorable conversations on the implications of female sexuality. Still, the topic – like the swirling whirlpool of feelings that is desire itself – remains a complicated one, with its significance tangled inextricably with the roles of women in society, and its overtones speaking lengths about our capacity to want. In light of this, several of the biggest titles this summer – and one excellent British tragicomedy – negotiate the bounds of female desire in all its weird and wonderful, ruinous and squalid, calamitously beguiling aspects. What is the place and the allure of the transgressive? And what are its consequences?

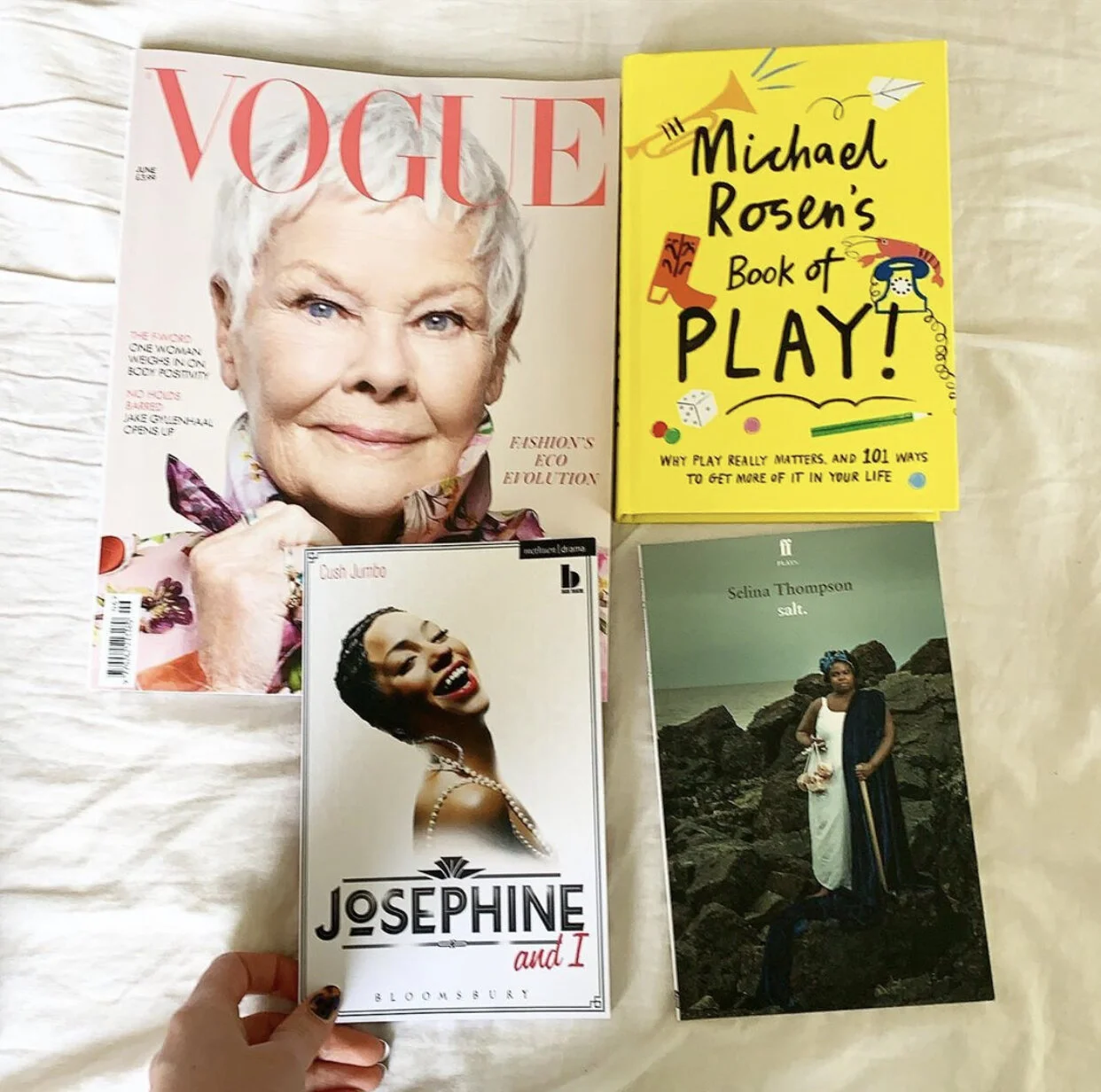

All images by Rachel Tay.

Towards the end of Bunny, Mona Awad’s surreal nightmare of a novel, pieces of its puzzle finally fall into place, and readers begin to see what it is that Samantha, our protagonist, wants. The scene opens with a confession of desire – of what had been alluded to throughout the story and which is now unravelling beyond the reins of the narrator’s alcohol-addled consciousness:

And then, embarrassingly, I begin to cry. Tell him everything. Embarrassing things. Shameful things. Anything to change how silent it was and the kind of silent it was. […] I sobbed like a child except I was a grown woman slurring these words into her lace thighs. Expecting at any moment for his silence to lift, the room to stand still, lighten, and right itself, a hand to reach out, a voice to offer some words of comfort and kindness. (271)

Filling the void with her words, the silence is at once suffused with a sense of shame and confusion. For the person to whom she speaks is her academic advisor – not a lover of whom she is making a passionate request – and the incident a crude parody of the unfortunate teacher-student romance trope in literature (groan), the reciprocation that she seeks is, alas, rendered ethically impossible under such circumstances. “Talking into a silence so loud it felt like a live thing in the room,” the rejection that Samantha faces – the mortifying repudiation of her inordinate wants – appears to manifest itself in a snarling chimera of anger, shame, and humiliation. “That seemed to be growing, gathering shape and shadow, no matter how much I kept talking like everything was fine” (271). Kept unrestrained, such is a passion that makes literal monsters out of loneliness.

“ Kept unrestrained, such is a passion that makes literal monsters out of loneliness. ”

Elsewhere in Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women, unconventional infatuations intrude upon, if not upend the scripts of normalcy – those dominant narratives of heteronormative love and happiness – which govern its titular dramatis personae’s lives. Here, female desire is not disregarded, but instead, grasped and manipulated by the heteropatriarchy. Maggie, in the most compelling story that Taddeo tells, finds herself acknowledging the immense gravity of an ill-advised affair with her high school teacher – and the devastating toll it took on her life – decades after its end. Similarly ensnared in the messy power dynamics between the sexes, Lina and Sloane negotiate for a domain in which their needs may be extricated from those of their respective husbands and lovers. Undeniably, then, Taddeo’s book does to some extent accomplish that which it proclaims to do: to “convey vital truths about women and desire” (x). Seeing as female sexuality has been so denied, if not pathologised, throughout Western history (consider Freud’s statement that a woman’s libido “often frightens us by her physical rigidity and unchangeability”), to want – and to know what she wants – is, for a woman, always a dangerously transgressive act.

Certainly, such a view has been criticised (and not unjustifiably) for its pessimistic and dated view of female desire. Nonetheless, I am inclined to wonder if desire, regardless of its origin’s gender, does not already imply a certain transgression? For the aching feeling of desire can solely exist in the moment that one attempts a grasp at something beyond reach, it can also be said to puncture the so-called sovereignty of the individual, rendering them helpless against that insistent longing which unsettles, destabilises, and makes one restless or besides oneself. That is to say, in desiring, one cedes control over the self to another. The difference between male and female desire – should such reductive categories even exist – hence, is that the former is far too often quashed by fulfilment and squared away into normative masculinist paradigms, whereas the latter must be relegated to the recesses of one’s mind. At this point, one also has to remember, crucially, that the conclusion of desire can only arrive with the possession of the desired object. Consequently, the treatment of desire as a problem to be solved merely imposes it as a demand for another’s indelible subjectivity.

This notion of incursion recalls Lara Williams’s Supper Club, which may be skillful in its luxuriant portrayals of women and the reclamation of their appetites, but had nevertheless left me hankering for an answer to the problem of – and here, I apologise for purloining Rosa Luxemburg’s thoughts – what happens after the party? For, at the heart of this novel are the bacchanalia-like celebrations that the eponymous group of women throw to satiate their hungers – sexual, spiritual, or otherwise – but one is left tempted to suspect the implications of such Dionysian chaos. This is not to say that I am not sympathetic to the characters’ conviction to reclaim a space wherein female desire can be both indulged and expressed, given its rampant suppression under current social conventions. Yet, when the supper club breaks into Selfridges for one of their most terrific feasts, leaving trashed makeup counters and decimated store displays trailing in their wake, one can only feel sorry for the poor shop assistants whom one imagines will have to pick up after the women the following day. In this sense, what I mean to suggest is this: that desire itself is a potent force, and the unleashing of which must always displace its effects onto another.

“what does one do with this unshakable presence of desire?

where does one put these feelings? ”

Original painting by Rachel Tay (2019).

Following this vein of argument, then, a single question remains: what does one do with this unshakable presence of desire? Or, to paraphrase Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s brilliant writing, where does one put these feelings? Such is a sentiment that the British comedy-drama television series, Fleabag explores, through its main character’s rampageous litany of sexual missteps, and in what might be one of the most moving depictions of female friendship on television. At a funeral for her mother, Fleabag turns to her best friend and admits:

Fleabag: I don't know what to do with it.

Boo: With what?

Fleabag: With all the love I have for her. I don't know where to put it now.

Boo: I'll take it. No, I'm serious. It sounds lovely. I'll have it.

Produced in the space between the two friends is one person’s insatiable yearning – a desire that the other cannot possibly effectuate for she is not its ideal object. Still, Fleabag’s words, once uttered, remain. They do not “drop to the floor,” spurned and uncontained, as Bunny’s protagonist’s do (Awad 271). But neither are they twisted in the mouths of their recipients. Instead, Fleabag’s desire is merely presented before Boo, lingering like words spoken in a confession booth – words that enact nothing but their own existence, just as facts confirm nothing but themselves. Hence, consider the now-infamous confessional dialogue between Fleabag and the (Hot) Priest:

The Priest: I don’t think you know what you want.

Fleabag: I know exactly what I want right now.

The Priest: What's that?

Throughout the second season, the back and forth, will-they-won’t-they flirtation between Fleabag and the Priest is so titillating for viewers, precisely because it toes the line of subversion. More than an infidelity in marriage or a professional conflict of interest, this relationship can be said to epitomise a forbidden fruit of the highest order. Recognising this, thus, the Priest tells Fleabag that “I can’t have sex with you because I’ll fall in love with you. And if I fall in love with you, I won’t burst into flames, but my life will be fucked.” A protest against Fleabag’s affections, the Priest’s resistance, however, belies the fact that he is already in love with her – a fact that is clear to all in the room, as well as the audience who has, for weeks, been watching the pair deny their mutual attraction. In this sense, every disavowal affirms, paradoxically, that which they cannot say, and every disclaimer acknowledges the preconditions that precede it.

For Luce Irigaray, these may be perceived as “contradictory words, somewhat mad from the standpoint of reason,” seeing as they leave one unable to “discern the coherence of any meaning” (29). Powerless as they are excessive, these are nonsensical words ostensibly rid of their performative ability. But as Cora Diamond writes of language, “There are some sentences that are nonsense but which would say something true if what they attempt to say could be said. The unsayability of what they attempt to say precludes it being said, but we can nevertheless grasp what they attempt to say” (158). The inutterability of Fleabag and the Priest’s feelings for each other – for who can allow or even conceive of such a religious indiscretion – therefore, does not undo their existence. Rather, desire simply nestles itself between each and every gesture exchanged between the lovers.

“love, however destructive it can be, does not necessarily have to destroy”

Perhaps this is what makes Fleabag’s ending such a satisfying one, and perhaps this is also where Phoebe Waller-Bridge succeeds far more than so much of contemporary literature in representing the messy, turbulent, and bewildering – but oftentimes still pleasurable – dimensions of desire. For love, however destructive it can be, does not necessarily have to destroy, and so the intense and agonising sensation of wanting another does not always have to be so unbearable, if only it can be consigned to a space outside of oneself. As the Priest himself declares, “Love is awful! It's awful. It's painful. It's frightening. […] So, no wonder it's something we don't want to do on our own. I was taught if we're born with love, then life is about choosing the right place to put it. '' Whilst he had chosen to ultimately place his faith in God, Fleabag – a staunch non-believer – has the harder task of deciding where and how to devote her love.

And so, she finally confesses to the Priest in the series’ final scene, in a rare instance of honesty moments before they part, “You know the worst thing is that I fucking love you. I love you. '' The tension here is so painfully palpable, for one does not know to which terrible outcome – the heart-breaking or the sacrilegious – it may lead. But before this revelation can call forth any reaction, and before the Priest can reply, Fleabag continues, “Let's just leave that out there just for a second on its own: I love you.'' Suspended amidst the silence, her desire is one that demands no correspondence, no reply, save for the Priest’s quiet acknowledgement. It calls for nothing and everything at once, for the both of them to refuse the consummation of – and thereby the tragic end of – their love. It is an utterance in which the inarticulable is nonetheless possible, and a space wherein love is always held in the process of becoming – carefully protected from its risks and repercussions, safely.

After two seasons of bad decisions, bad sex, and even more disastrous love affairs – all driven by an implacable desirous impulse – it is thus comforting to know that Fleabag’s love has, at last, even if only temporarily, found a place in which to settle. In this way, for all the cynical platitudes that other literature might inspire in me, I suppose Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag offers me one thing left to say – that is, “Being a romantic takes a hell of a lot of hope. I think what that means is, when you find somebody that you love, it feels like hope.”

Born and raised in the perpetually summery tropics — that is, Singapore — Rachel Tay wishes she could say her life was just like a still from Call Me By Your Name: tanned boys, peaches, and all. Unfortunately, the only resemblance that her life bears to the film comes in the form of books, albeit ones read in the comfort of air-conditioned cafés, and not the pool, for the heat is sweltering and the humidity unbearable. A fervent turtleneck-wearer and an unrepentant hot coffee-addict, she is thus the ideal self-parodying Literature student, and the complete anti-thesis to tropical life.

Reading Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times and Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies, Rachel Tay explores the unease of moving away from one’s own country and language.