The Art of Intimation: On the Intimate Languages of Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times and Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies

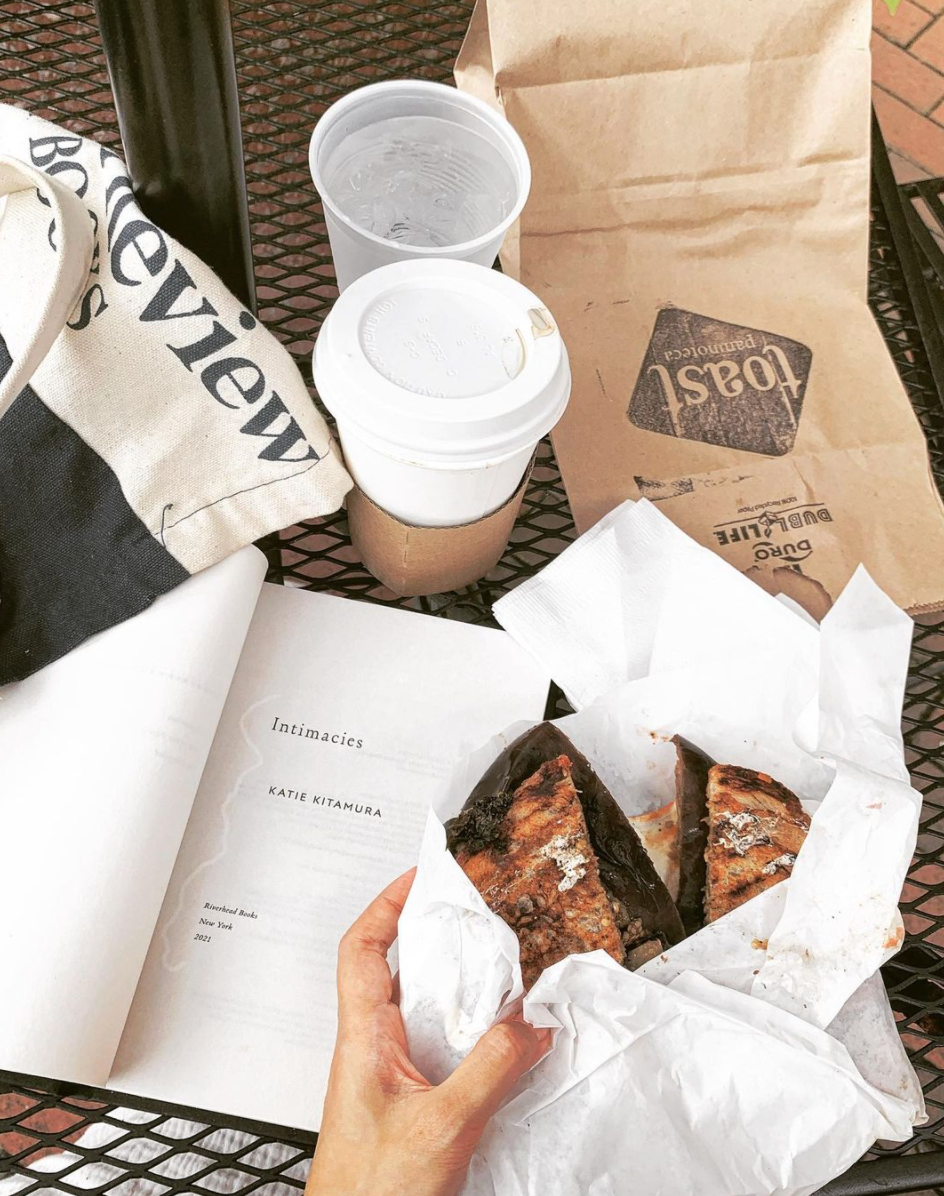

Photograph by Rachel Tay

“When one is no longer at home in one’s language, nothing is certain”

When one is no longer at home in one’s language, nothing is certain — this is the common premise from which both Naoise Dolan and Katie Kitamura’s most recent works proceed. Taken abroad by their careers and dislodged from a culture familiar to them, the respective protagonists of these novels find themselves buoyed along by currents of contingencies, even as they are inevitably confronted with momentous life decisions: while their present preoccupations demand commitment from them, their accented tongues remain a lingering reminder of how temporary such configurations may be. Ensnared in the interstices between words, everything is rendered ambiguous. Is it any wonder, then, that it is in the alchemy of one language into another that these otherwise disparate stories reside?

The delicate functions of interpretation figure saliently in both novels. In Dolan’s Exciting Times, twenty-two year old Ava contemplates the colonial baggage of the English language when she, an ESL teacher and an Irish expat, is paid to impart a language forcibly imposed upon her to the children of Hong Kong’s ruling class. “The English taught us English to teach us they were right,” she quips in one instance, “I was teaching my students the same about white people. If I said things one way and their live-in Filipino nanny said them another, they were meant to defer to me.” It is thus evident that the confluences of race, class, and history in linguistic circulation is not at all lost on Dolan’s wry protagonist.

Similarly, interpretation is displayed front and center in Kitamura’s Intimacies, as its unnamed narrator anatomizes her work as an interpreter for the International Court of Justice. Challenged by a former president on trial for his unspeakable war crimes, and whose words have nevertheless been entrusted to her, she pronounces that “[m]y job is to make the space between languages as small as possible,” “to ensure that there would be no escape route between languages.” With the nuances of language therefore alien to neither, the gaps and fallibility of linguistic interpretation gleam markedly in these two women’s self-reflexive narrations. For these initiated wordsmiths, every word must be purposeful, deliberate.

Yet, the flipside of such an attentiveness to language is also the invariable knowledge of its ultimate futility: that signification is a process of inadequacy and overcompensation, and that all acts of communication are composed only of lucky guesses or unfortunate misunderstandings. For, if “interpretation” is what narrows the “space between languages,” as Kitamura defines, then it should only follow that crevices still persist between what is said and what is received. “Everyone wants to be understood,” the blurb of Intimacies splashes in a hot pink font across the front flap of the book’s jacket. But the novel acknowledges that a completely cogent understanding can only exist as such — as unfulfilled hope. Where Kitamura’s narrator strives for exactitude and clarity in her work, the miscommunications suffused throughout her personal life go on to reveal the enduring frays at language’s edges: propelling the novel’s narrative is, alas, an unreplied text, a note of silence from a lover with whom she has a complicated agreement, a lacuna that she is called to fill. In this quintessential drama of imperfect human connections, much remains to be intimated and implied. Accordingly, what is left unsaid becomes at once urgent and evocative.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the novel’s concluding dialogue, a sparse yet significant conversation between the narrator and her partner regarding their future prospects. Here, Kitamura’s prose is thin, its careful restraint betraying, however, an overflow of desire and inarticulable tension. “[A]lthough there were things that I had intended to say to him,” her narrator concedes, “words that I had believed needed to be spoken between us, I said only this: I understand.” The resulting effect is almost Austenian. Recalling Knightley’s declaration in Emma that “If I loved you less, I might be able to talk about it more,” the paucity of language in this exchange circumscribes, instead, a space for feelings that one cannot bear to articulate. Because its admission will effectively concretize its existence — while at once drawing her partner into an irreversible relation — the truth of the narrator’s sentiments can only inhere in her unspoken words.

After all, intimacy is always inconvenient. That is to say, the possibility of inconvenience is always inherent in all our interpersonal connections: one is made reliant on others, in the same way that one becomes culpable for them. It is hence no coincidence that readers encounter both Kitamura and Dolan’s protagonists in relationships framed not only by their indispensable romance, but also by the financial support as well as the unsettlement of the traditional couple structure that these unusual arrangements bring. Seeing as the amalgamation of their private lives with such tangible objects appends the former to more fathomable stakes, the liability latent in these private affairs is correspondingly made manifest. In this way, the fact that both characters’ material circumstances are — despite the undefined statuses of these liaisons, and to various, tricky extents — dependent on their partnerships, cannot help but loom large over their lives.

Having drafted and deleted several texts to Julian — a friend with whom she is sleeping, and in whose apartment she has taken up residence — for instance, Ava divulges to us in Exciting Times that

We chose what to share. Through composition I reduced my life, burned fat, filed edges. The editing process let me veto post hoc the painful, boring, or irrelevant moments I lived through. Necessarily Julian curated what he told me, and that, too, made me happy. Together we were making something small and precise.

Comprised as much of what is omitted as that which is conveyed, the stories that Ava and Julian tell of themselves are therefore defined by a fiction and a wish. In each unsent message that Ava composes — and every ponderous pause in Kitamura’s novel — lies a covert impetus to preserve an ideal relation without burdening the other with oneself. Yet, this is a fundamentally impossible task, seeing as the impulse of every attachment is not simply one’s willingness to be open to another, but the unexpressed desire that the other will do the same for oneself. Thus, when caught by another lover in the process of typing one such missive — in the ellipses that “waved like trills on Chopin’s staves” — Ava admits that “the prospect [of being seen] should have horrified me … [but] I wanted her to know.” One wants for one’s intimations to be nonetheless heard, just as one wants for others to intuit the implicit and unexposed contours of one’s own vulnerability, for such is the structure of intimacy anyway. It, as Lauren Berlant writes in an early essay on such intricate relations, “involves an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about both oneself and others that will turn out in a particular way.”

Elaborating on their work in a more recent talk, Berlant points out that this urge to draw others into the worlds that one imagines — to plunge oneself headlong into the messy and labyrinthine interpersonal dramas of one’s lives — stems from what they call “an inconvenience drive.” “We want to be inconvenienced by the very people we want to be inconvenienced by,” they tell us, “It is about receptivity. It is about who you want to let in, and how you process it, and what you do with it.” What is implied as a result in this formulation of our human inclination towards sociality — that “want to be inconvenienced” — is the concurrent and even more inconvenient awareness that one can similarly present to others. Consequently, the intimate proximity of being with another can be said to exist only in the constant approximation that one must make of one’s place in all relationships. Likewise, the hope of community bespeaks only the hope for one’s projections of the future to align in congruence with those of others’.

In this unrehearsed waltz of wants, needs, and ineffable desires, it hence appears that we can only aspire to a serendipitous synchrony. Still, if these two novels by Kitamura and Dolan are anything to go by, we cling on to such moments of intimacy to hold out for the possible. Unmoored and unrealized, the implications of our unspoken words remain to be thought and navigated: they intimate the potential for renegotiated relations, for worlds that might, one day, be sufficiently capacious to encompass oneself. So we reach to the “yes” and the “yet”, as these writers ultimately do, for “a glimmer of hope. That we might yet proceed from here. That this might yet be enough” for the dust of language to settle around oneself, and for one to finally feel at home in the world — even if only in time to come, even if only possibly (Kitamura).

A fervent turtleneck-wearer and an unrepentant hot coffee-addict, Rachel Tay is the ideal self-parodying Literature student, and the complete anti-thesis to tropical life in Singapore, where she was born and raised. She is a frequent contributor at The Attic on Eighth.

Reading Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times and Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies, Rachel Tay explores the unease of moving away from one’s own country and language.