Letters to Mother: Children Writing Across the Boundaries of Language and Memory

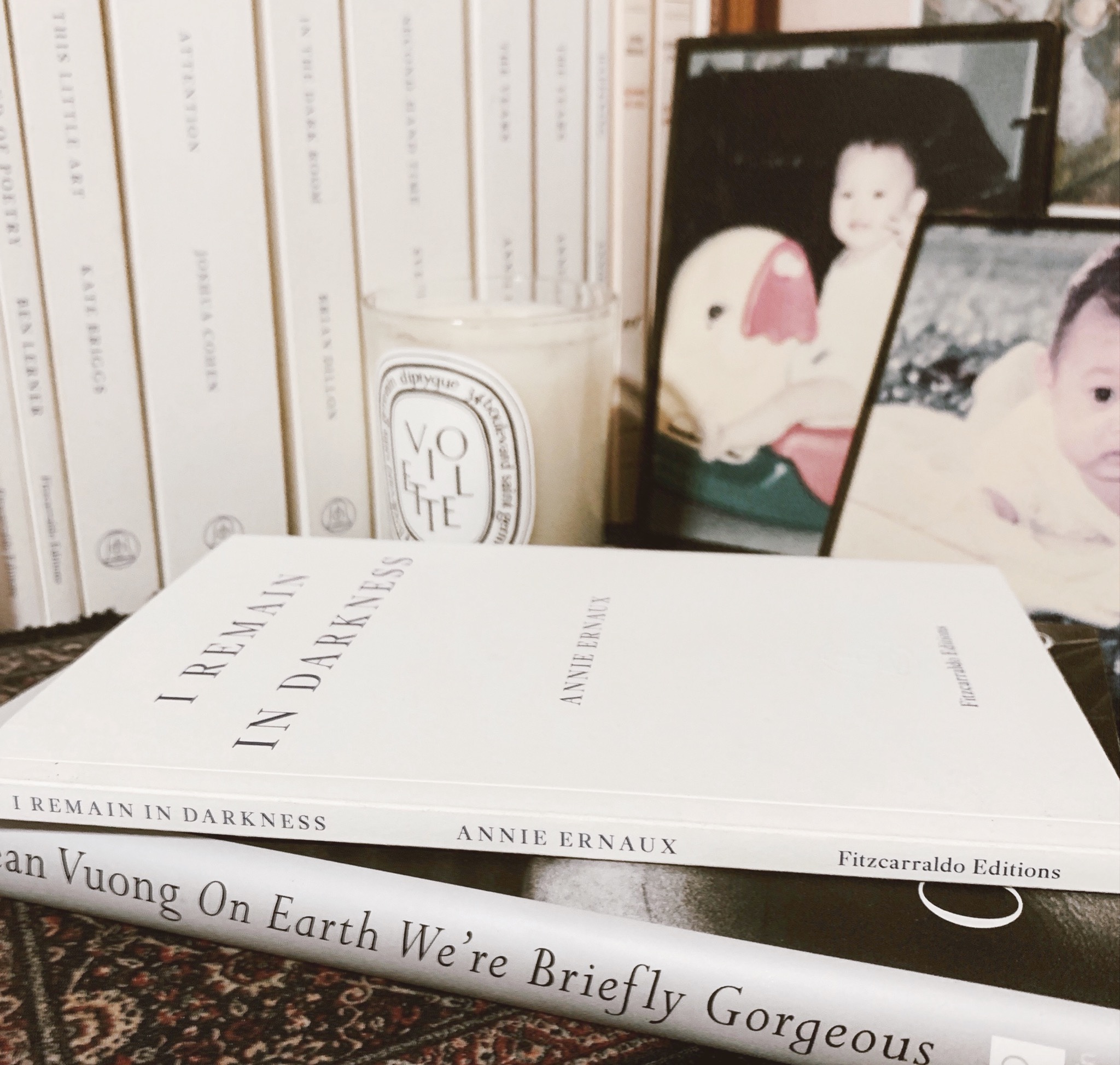

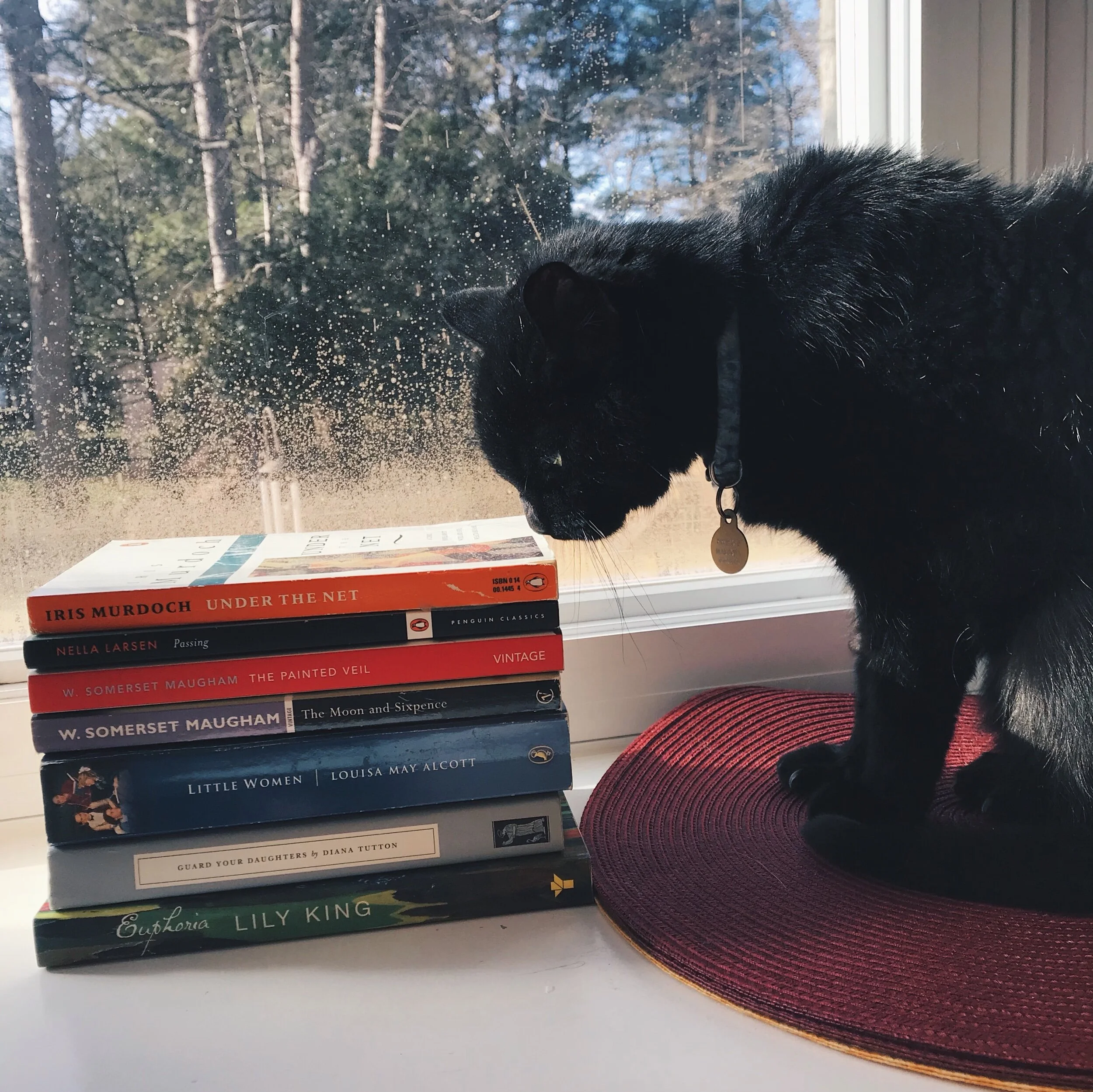

Image by Rachel Tay.

“I have known the body of my mother, sick and then dying.”

i

On October 26, 1977, the day after his mother’s death, Roland Barthes began writing what would eventually become his Mourning Diary. Having been scribbled on flimsy slips of paper, the entries that follow are short and terse. The above epigraph, for instance, is a reply to the charge that “You have never known a Woman’s body,” forming one half of an exchange that appears peculiarly untethered from its source. Abstract and aphoristic, Barthes’s fragments are the effect of a language irrevocably sundered. For how can a child ever write of their parent’s death, seeing as it demands that one imagines the lacerating absence of their very origin? Speaking rather aptly to this question, Annie Ernaux then describes the process of keeping a diary in the final years of her mother’s life, “Towards the end of 1985, I began writing the story of her life, with feelings of guilt. I felt that I was projecting myself into a time when she would no longer be.” The resulting record, I Remain in Darkness, can be said to be the French writer’s personal Mourning Diary. The only difference is that Ernaux tells of a mourning before the fact, a premature knowledge of loss that commences just as the onset of Alzheimer’s atrophy begins to creep upon her mother’s body and mind. As a result, what emerges is a daughter’s affecting struggle to recover the irrecoverable.

“how can a child ever write of their parent’s death, seeing as it demands that one imagines the lacerating absence of their very origin?”

As with The Years and Happening – the first two English translations of Ernaux’s work to be published by Fitzcarraldo Editions – time and memory serve as the capricious anchors of I Remain in Darkness. But where the former, conceived as a resistance against time’s corrosive maws, wrestles with the inevitable destruction of memory’s archive, the latter is far more uncertain about its memorialising impulse. “Since I decided to tell her story,” states Ernaux, “I have been unable to write anything… I am seized with panic whenever I think of her. I am afraid she is going to die.” Should her mother be the sole receptacle of her memories, it would also follow that to recreate her past is akin to displacing her from her own being. But what alternative is there apart from this impossible act of retrieval, when memories cannot cease to leak from one’s mother’s mind. In this sense, as she begins to trade roles with her mother – to clothe, feed, care for, and mother her ailing mother however reluctantly – she, too, becomes her mother’s dispossessor: “I am overcome with remorse … she’s my mother and somehow she’s not quite my mother anymore."

“Yet, it is also in this wavering that one encounters the author in her most tender state, for it is exactly in her hesitance to write of – and to therefore acknowledge – her mother’s oncoming death that Ernaux finally betrays a glimpse of her fragile, child-like vulnerability.”

In her own words, Ernaux is at once guilty and proud, cruel but at the same time “appalled by [her] own cruelty.” Underlying every account of her visits to the geriatric ward, it seems, is that self-accusatory cry of “how could you?” Yet, it is also in this wavering that one encounters the author in her most tender state, for it is exactly in her hesitance to write of – and to therefore acknowledge – her mother’s oncoming death that Ernaux finally betrays a glimpse of her fragile, child-like vulnerability. Insofar as children must eventually come to face the inexorable truth of their parents’ finitude, they are nevertheless still children, in the same way that Ernaux is still a girl who needs her mother. “The situation is reversed, now she is my little girl,” she writes heartbreakingly, “I CANNOT be her mother.” She cannot usurp the position of her parent, for not only is this literally unconscionable, it also asks that she erases all vestiges of her mother as mother from memory. Thus, this is a text that undeniably argues with itself about its own imperative. But more than that, it is also one that betrays through its reticence an even deeper sense of helplessness – one so utter that it transcends Ernaux’s mother’s growing incapacities. In other words, this is as much a document of a woman’s life at its end, as it is the searing and final closure of her daughter’s childhood.

ii

In Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, we find yet another stirring negotiation of an author’s relationship with their mother – another futile reach across an impassable border. Only here, it is not only time but also language that divides parent and child. For if the passage of time, for Ernaux, brings her closer to her mother’s instant of death, it also carries the narrator of Vuong’s story – a young Vietnamese-American nicknamed Little Dog – towards a country, culture, and language that would veil the respective histories of both mother and son from each other.

“I am writing to go back [in] time.”

As the epistolary novel opens, “Dear Ma, I am writing to reach you – even if each word I put down is one word further from where you are. I am writing to go back [in] time.” And so the text begins by beginning again, by returning its narrator to a past told fantastically in an amalgam of myths and memories to him, and by reconciling mother and son with each other. Except this letter, as readers come to realise, will never be read by its intended recipient, seeing as “at five,” after a napalm raid that collapsed her schoolhouse, the narrator’s mother “never stepped into a classroom again.” A blend of rudimentary French and Vietnamese hence passes between the two, whereas English alone stands for his mother’s alienation from him and from America, a source of his mother’s painful humiliation.

“I took off my language and wore my English, like a mask,” says Little Dog, “so that others would see my face, and therefore yours.” Strangely enough then, even as the book is addressed to his mother, it appears that it is for us – and perhaps, for himself as well – that he renders his addressee legible. That is, as intelligible as he himself can fathom from the kaleidoscope of songs and fables that masks the trauma of his heritage, and as unambiguous as a language altered irreparably in translation. For “some things are so gauzed behind layers of syntax and semantics, behind days and hours, names forgotten, salvaged and shed, that simply knowing the wound exists does nothing to reveal it,” Little Dog can only guess at his past, the phantom-like foundations that have nonetheless led him “here, to this page, to tell [his mother] everything [she’ll] never know”. Hence, the work of a child, and especially a child of an immigrant, is ostensibly always an interpretive one.

But this only presumes the loss of an original meaning, a failure at the origin. One could even say that it is this imperfection that necessitates the existence of the child – the child who twists and turns, who tells and retells a patchwork of memories, and who carries on their genealogy in them – because it is only in this figure that the possibility of a future perfection may be invested. To this end, children are to their parents “a death that won’t finish, a death that keeps dying as we walk past it to relieve ourselves,” a means of living on. Thus, recombined in the labyrinthine and exquisite language of Little Dog’s narration, ancestral tales and traumatic histories alike – the same precious stories that form the very constitution of his being – become, as the title says, gorgeous.

iii

“One does not give birth in pain, one gives birth to pain,” wrote Julia Kristeva famously in ‘Stabat Mater’, her essay on maternal abjection and motherhood, “the child represents it and henceforth it settles in, it is continuous.” In this sense, should motherhood promise a painful rupture of the self, a perpetual opening on the mother figure, then the child, in turn, must become the wound. Between Annie Ernaux and Ocean Vuong – a diary and a letter, each centred around a mother’s life – therefore, are two accounts by children, separated by context but both equally compelling, on what it is like, or how it feels, to be and to embody their mothers’ pain. This is not to say that either of these authors ever come close to conveying the truth of motherhood – to do so would be disingenuous, and besides, countless other authors have written recently on the topic. But rather, these are texts on pain as composed by one isolated from the experience of it; they convey an awareness of a suffering that one can never feel for themselves.

“As insensible grief takes over [...] readers are left, consequently, with the dull and infinitely prolonged ache of a tie severed. ”

As Ernaux reveals in her prologue, “I remain in darkness” (“je ne peux pas sortie de ma nuit”) was the last sentence that her mother ever wrote. And perhaps this is the only sentence that really matters in both this review and the entire book. After all, it should only be so prophetic that a parent situates herself within an incommunicable void, prefiguring an incomprehensibility that will simply become absolute after her death. Proceeding from this assumption of incoherence, hence, what remains is not only a daughter’s confusion, but her astute and introspective recognition of this failure of knowledge. As insensible grief takes over and words flounder – become too totalising or too banal – readers are left, consequently, with the dull and infinitely prolonged ache of a tie severed. Swimming in language and time, to desperately keep alive she who sustains oneself – this never-ending feeling of encircling, of anxious deliberation, of mourning and peering into the darkness to find mere shadows there – it thus seems, is exactly the terrifying yet poignant condition of being a child.

Books reviewed:

I Remain in Darkness by Annie Ernaux

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

All opinions are the writer's own, however she was kindly gifted a review copy of I Remain in Darkness. Thank you to Fitzcarraldo Editions!

Born and raised in the perpetually summery tropics — that is, Singapore — Rachel Tay wishes she could say her life was just like a still from Call Me By Your Name: tanned boys, peaches, and all. Unfortunately, the only resemblance that her life bears to the film comes in the form of books, albeit ones read in the comfort of air-conditioned cafés, and not the pool, for the heat is sweltering and the humidity unbearable. A fervent turtleneck-wearer and an unrepentant hot coffee-addict, she is thus the ideal self-parodying Literature student, and the complete anti-thesis to tropical life.

Reading Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times and Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies, Rachel Tay explores the unease of moving away from one’s own country and language.